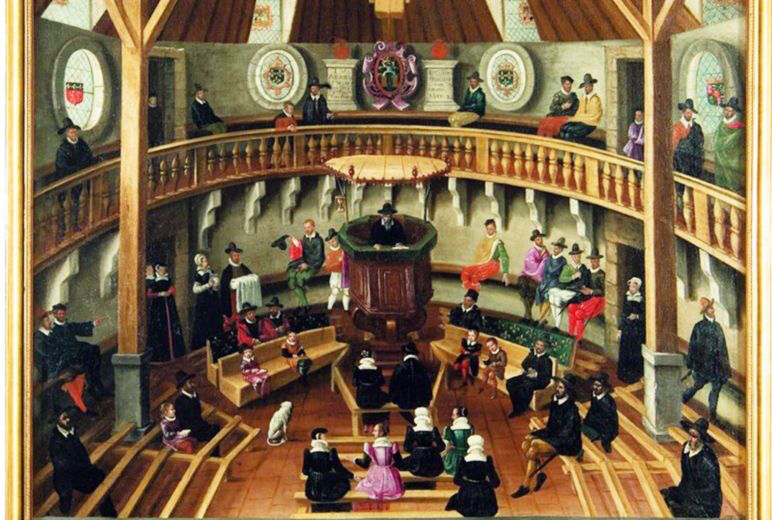

The Calvinist Temple de Paradis, Lyon, by Jacques Perrissin, 1564

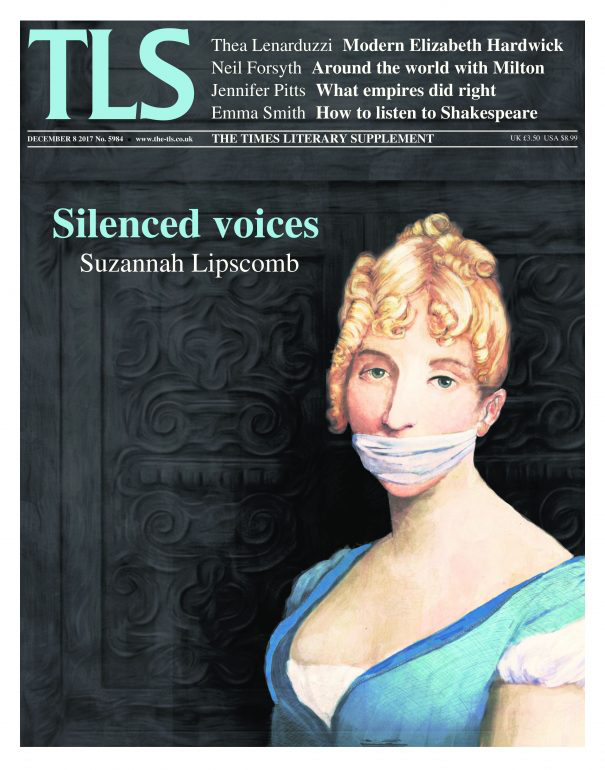

Silenced voices

SUZANNAH LIPSCOMB

Most of the women who have ever lived left no trace of their existence on the record of history. In sixteenth-century Europe, it is likely that no more than 5 per cent of women – at most – were literate; ordinary women left no letters, diaries, or notebooks in which they expressed what they felt or thought. For us, their voices are silent.

From the mid-1530s, and especially from the 1550s, ordinary women and men in France started converting, in ever increasing numbers, to Calvinism. The Calvinists rejected the authority of the Pope, abhorred the Catholic Mass, and deplored what they saw as the corruption, hypocrisy, and idolatry of the Roman Church. Their Catholic enemies mocked them with the name “Huguenots”.

Protestantism spread fast in the south of France, especially in the Languedoc. In Nîmes, 8,000 people – roughly two-thirds of the population – gathered in 1561 to hear the famous Protestant cleric, Pierre Viret, preach. By the end of that year, some 50 per cent of Nîmes’s population had converted to Calvinism. These recruits included the local elite. By early 1562, 60 per cent of the twenty-six judges of the city’s présidial court (which had jurisdiction over minor criminal and civil matters) were Protestant, and, by 1563, Huguenots dominated the town council.

Such Calvinist popularity was not unique in the Midi. In Toulouse, it is estimated that one-seventh of the 35,000-strong population were Huguenot by 1562 – but that number would soon decline rapidly. The reason for this reversal was that, after Catherine de’Medici’s granting of legal toleration to Protestantism in January 1562, a confrontation between the Catholic nobleman François, duc de Guise, and a group of Protestant worshippers inside the walls of the small town of Vassy on March 1, 1562 ended in the death of fifty people. The massacre marked the first turn of the cycle of the deadly religious wars that would recur repeatedly across France over the next four decades. The worst incident of the wars was the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of August 24, 1572, in which Catholics killed 3,000 Protestants in Paris, and another 7,000 across France, in episodes of brutal, sickening violence, over the space of four days. Understandably, many former Protestants apostatized.

But in the south, certain cities retained their Calvinism, among them Nîmes and Montauban. In Nîmes, when a massacre occurred in 1567, it was of Catholics by Protestants. On September 30, the Nîmois Protestants seized control of the city gates, shouting “Kill! Kill the papists! New world!”; imprisoned all the leading Catholics; and slaughtered at least a hundred of them, leaving their bloody corpses to rot in the well at the bishop’s palace. Given the relative populations of the cities of Nîmes and Paris, this was proportionately nearly as bloody as the events of 1572. Full control of the city – town council, consuls and court – moved firmly into Protestant hands.

Surrounded by, and regularly under attack from, Catholic forces, the rebel Protestant cities tried to survive with their religion intact in a hostile world. The chief way that inhabitants sought to distinguish themselves from their Catholic enemies and protect themselves from the wrath of God was to adhere to a strict moral code. In areas where Protestant power was at its strongest, therefore, the Calvinists established a mechanism for the imposition of morality, and for disciplinary action in the case of failure: the consistory, a form of church court. Although the consistories also functioned as the governing bodies and welfare centres for the local churches, the vast majority of their time was absorbed in moral supervision, interrogation and reprimand.

Each consistory consisted of around ten to eighteen men – ministers, elders, deacons and a scribe – who met frequently: in Nîmes, they gathered fifty-six times a year. The consistory’s elders were charged with policing a handful of local streets and reporting any wrongdoing to the panel. Routine gossip was carefully investigated. Every indiscretion was recorded. Anyone guilty of the slightest impropriety could expect to be summoned before these self-appointed arbiters of morality.

The immoral were punished through a graduated series of shaming penalties, from private admonition, public reparation before the congregation, temporary suspension from the Eucharist, and, for the obstinately recalcitrant, permanent excommunication. These may seem light by comparison to contemporary criminal sentences, which were generally corporal or capital – but evidence tells against this understanding. Repentance entailed a display of humility that compromised personal honour and was consequently dreaded. When a butcher, Jehan Mingaud, confessed his adultery with Suzanne Bertrande to the consistory in Nîmes in 1589 and was ordered to repent before the whole church the following Sunday, he protested that the consistory was being “too severe against him” and that he would “prefer to suffer death immediately than make the said public reparation”. This form of punishment actually aped sentences dealt out by the criminal courts. In Montauban, the register of criminal sentences pronounced by the consuls of the town indicates that secular justice also punished fornicators by the “amande honorable la torche au poing a genoulx” – that is, a public apology traditionally made in a church by an offender on his or her knees, holding a torch in one hand, in a state of undress, and with a rope around his or her neck. In addition, the church and civic authorities clearly worked together. A surviving register of criminal sentences for Montauban shows cases of paillardise (fornication; from the French paille for hay, as in “rolling in the hay”) appearing in both that register and the consistorial records: some offenders were being punished twice.

The upshot of this rigour is a series of consistorial records full of interrogations of the guilty, the innocent and the witnesses, which have survived to this day. I have studied thirty-five volumes of consistorial deliberations – some 8,728 pages – from ten cities and towns in the Languedoc between 1560 and 1615. The major series are the consistorial records of Nîmes, which are not only some of the best surviving collection of consistorial registers in existence, but among the best records of the way common people lived their lives in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Europe. These registers rival better-known surviving court and inquisitorial records – such as those from the medieval French village of Montaillou, about which Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie wrote – in richness and insight. Yet, as a body of evidence, historians have neglected them: I am the third historian to read these manuscripts, the second to do so at any length, and the first to use them to explore the lives of ordinary people, and, above all, women.

Women were thought to be primarily responsible for sexual and other sins, so controlling morals meant controlling women. This means that the registers include over a thousand testimonies by and about women, most of whom could not write and left no other record to posterity. In responding to charges of sin or in testifying against others, women offered descriptions of their daily lives, and justifications for their behaviour.

Such testimonies are of great value because problems of evidence have dogged attempts to understand the lives of the ordinary people who made up early modern society. Women’s voices, in particular, must be searched for in vain in the parish registers, notarial and judicial records, tax rolls, conduct books and statutes that have constituted most of the evidence available to the early modern historian. Such sources are too formulaic and prescriptive to allow much insight into the behaviour and mentalities of ordinary women.

But the consistorial registers allow precisely that. It is possible to explore the mental outlook and lived experience of women in early modern Languedoc, particularly considering their attitudes to, and experience of, gender, sexuality, marriage and family, through the direct testimony of the women themselves. The women’s voices heard through the con sistories are those that appear nowhere else, because women could initiate cases, as they could not before most criminal courts, and there was no fee to approach the consistory, so it was open to the poor.

Women also feature prominently because of an unintended consequence of the consistorial system: it empowered them. Women quickly learnt how to use the consistory: they denounced those who abused them, they deployed the consistory to force men to honour marriage promises, and they started rumours they knew would be followed up by the elders. The consistorial registers, therefore, also let us see how independent, self-determining and vocal women could be in an age when they had no legal rights, little real power and few prospects.

One example is Magdaleine Sirmiere. Magdaleine was summoned before the Béd arieux consistory in July 1581 for idolatry – having attended Mass – and for dancing. She confessed to both faults, was exhorted to submit herself to the discipline of the Church, and to marry her fiancé, Guillaume Puech, a tailor. To this, she made no response, and so the church authorities instructed her to “think well and ask God”, and to return to the consistory with her response within a week. This she did not do.

Consequently, her mother, Lyonne Martinne, and brother, Antoine Sirmie, were summoned in her stead. Both were ordered to persuade Magdaleine to face the Church’s discipline and to marry her fiancé. A week later Magdaleine showed up to the consistory, but when asked whether she would submit to the censure of the Church, she claimed not to know to what she would be submitting herself. The consistory threatened her with suspension from the Eucharist and gave her another week to shape up. The week passed and, once again, she did not appear.

Her more acquiescent brother presented himself in late August and bore the brunt of the consistory’s anger, being threatened with suspension if he failed to persuade her to comply. Finally, when the consistory’s patience was running thin, Magdaleine reappeared before the assembly on September 2, declaring herself sorry for having attended the Mass and for dancing, and willing to submit to the authority of the consistory and do as “will be ordained and advised by the company”.

As to Guillaume, however, she stated that she did “not wish him harm, but with regard to marrying him, she does not want to do it, because God does not want it”. The consistory quickly retorted that God did, in fact, not only want, but commanded her to marry Guillaume and that it was a blasphemy to use God’s will to justify her stubbornness. She was promptly suspended from the Eucharist because of her “rebellious heart”. Yet Magdaleine clearly persisted in her refusal for, five months later, Guillaume appeared before the consistory to renew his claim to Magdaleine, and threatened to appeal to the magistrate. Whether he was ultimately successful in his claim on her is hard to judge: the register of marriages for Bédarieux sadly falls silent between 1582 and 1589, while the baptismal records are no more conclusive.

The records do, though, give some indication of why Magdaleine might have wanted to terminate the engagement. There are two earlier references to the couple before this series of events. In December 1580, Lyonne had been instructed to do her motherly duty and to instruct her daughter to complete some unnamed task (presumably marriage). In January 1581, the consistory recorded that Guillaume had beaten Magdaleine. He had apparently justified his actions by saying she had told him “that she did not fear him” and he wanted to remind her that she should. Consequently, she did not want to “yield to the accomplishment of their marriage”. Magdaleine’s resistance to marrying had lasted for some time and there were very good reasons for it.

Her subsequent interaction with the religious authorities demonstrated the same lack of fear that she had shown to Guillaume: it was conducted on her timetable, not theirs; she feigned ignorance when wishing to avoid capitulation, but submitted, in part, to their charge when it was convenient for her to do so; she held to her position on marriage for well over a year, despite intimidations and pressure from the Church, her family and her fiancé; and, above all, she justified her behaviour on the grounds of divine revelation. In so doing, she made an inherently comparative claim about her relationship with God and that of the consistory. Given a choice between obedience to the Church or to what she saw as the will of God, she chose the latter. In this, Magdaleine Sirmiere asserted a spiritual authority that the consistory could not accord her: her untrammelled female piety took a form that did not suit the religious notions of the male authorities (and one which exposed their limited commitment to the Protestant doctrine of the “priesthood of all believers”). Her belief system was one in which God was accessed directly – it was not a vicarious or passive faith – and it was one that she could use to justify and legitimize her decision to maintain control over the course of her life. It demonstrates that religious resistance to the Church was not solely the province of the elites. Ordinary women, too, could have rebellious hearts.

Not all the women in these pages are such obvious heroines. For all those who sought to break off an engagement, there were others seeking rather to force a reluctant man to marry them and turning to the consistory in the hope of support. Many, no doubt, had genuine grievances. It is not clear that this is the case for a servant called Jehanne Fontanieue, who presented herself at the consistory in Nîmes in December 1562 to protest against the proposed marriage of a carpenter called Jacques Rosilles. Jehanne claimed that she and Jacques were betrothed, and on the promise of marriage, she had “abandoned herself” and submitted to Jacques’s advances, and that since then he had “known her three or four times a day” – a claim so eyebrow-raising that her testimony rings false to modern ears, but not to the consistory. Although she could provide no evidence of the alleged engagement promises, neither eye witnesses nor gifts, nevertheless, the consistory summoned Jacques, Jehanne’s father, and a man called Lazaire Fazendier, whom Jehanne had nominated as supporting her claim.

When Jacques was questioned, he said that when he’d been working at the Château de Saint-Genieys where Jehanne was a servant, another employee, Jehan Dussoyre, had asked him if he had ever thought of marrying Jehanne, and said that, if he did, he’d stand to gain Jehanne’s parents’ wealth via her dowry. According to Jacques, this conversation was only “in the manner of passing the time and without any intention to marry her at all”. This was male banter, in which they assessed the relative merits of women and their financial value. Jacques denied ever having had sexual intercourse with Jehanne, or making binding promises to marry her before witnesses, but he did admit that he said to her that he would marry her if her parents wanted to give her a good dowry. He claimed, however, that this was a statement extracted from him under sufferance, when Jehanne was surrounded by her people whom Jacques did not want to displease – he was convinced, he alleged, that they meant him ill and would take him prisoner if he did not go along with the plan, and he felt threatened because, not being in his home town, he had no support.

Yet the consistory had obviously heard lurid rumours that belied his words. They enquired as to whether he’d had carnal intercourse with Jehanne “behind the old tower of Saint-Genieys”, if he had promised to marry her one Sunday in the base court of the château before witnesses, and if he had told her to take care of “the fruit of her womb” (a pregnancy) – all of which he fiercely denied. Outraged, Jacques accused Jehan Mantes, who he said owed him money and was a fornicator, thief and a pimp, of conjuring up these allegations to spite him.

Confounded by the differences in the accounts, the consistory brought the couple face to face. They were pointedly asked to swear to tell the truth. Jehanne swore, and then boldly put it to Jacques that he must remember when she had dropped off some white shirts to his workshop and he had “known” her carnally for the first time. He denied it, and added that “he took God as his witness”.

This planted a seed of doubt. After Jacques left, Jehanne was asked who had counselled her to oppose Jacques’s marriage and to try to secure him as her own husband. These were accusatory terms. She responded that her father, her friends and Lazaire Fazendier had given her such counsel. The consistory called her father, who admitted he had not heard the betrothal promises in person himself, but had been told of them by his daughter. The consistory then sent their summoner to speak to Lazaire Fazendier. Fazendier was just mounting his horse to travel outside the city, and spoke only a few words: that he did not have anything to add, and they should look diligently at the evidence and pronounce justice. In short, no one could supply definitive evidence of an engagement, and both men covered themselves, rather than supporting Jehanne. As a final sally, the consistory recalled Jacques and asked him again, “in the name of God and in all conscience”, if he ever promised to take Jehanne in marriage or slept with her. He again said no, and repeated his powerful assertion that he “took God as his witness”. In the absence of any concrete evidence, it was her word against his, and, while the consistory manifestly felt some hesitancy about making their pronouncement, finally, after much discussion, they concluded in Jacques’s favour.

The insights in the folios of the consistorial registers take us to the heart of women’s social, sexual and marital lives – to their relationships with God, with their husbands and lovers, with their children, and with their friends and community. This evidence allows us to explore and analyse the behaviour, attitudes, thoughts, feelings, motivations, values, beliefs and strategies of these women. We can examine how women understood and made sense of their everyday lives, how they talked and thought about events, and how they sought to act when things went wrong. We see how ingenious and bold they were, and how determined to dictate their own fate in matters such as their control or enjoyment of sexuality, their choice of marriage partners, or their idiosyncratic spiritual decisions about what they believed. The records testify to women’s vociferously executed judgements on fiancés who abandoned them and husbands who failed them, on employers who abused them, or on other women who failed to meet womanly ideals.

By recording moments of social fissure, whether the breakdown of neighbourly relations, illegitimate pregnancies, broken engagements, malicious gossip, or marital quarrels, these registers permit us to access the realities of society, family and culture. Ladurie described the value of the testimonies of the villagers of Montaillou as “pointillism” – tiny dots that together produce a great degree of luminosity and brilliance of colour. Taken together, the evidence from the registers of Nîmes and the rest of the Languedoc, also produces such luminosity and allows us to examine matters of love, morality, sex, belief, suffering and social relationships among ordinary women living in an age of violence and upheaval. Their voices can be heard again.

From: https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/public/magdaleines-dance/